ne of my earliest ambitions when I was a child was to become a detective. I read lots of detective stories growing up, and it seemed like a pretty exciting life. You got to follow people and figure out what they were up to. That appealed to me since I was a nosy kind of kid and already spent quite a bit of time spying on the people next door. Also, you could collect clues and put them together to solve a mystery, just like Nancy Drew did. That seemed really satisfying.

When I was about ten, I traded in that career idea for a new one: newspaper reporter. I'd discovered that I liked writing, and that was the only job I could imagine where you could write. (Writing books seemed completely impossible.) I didn't really think I could be a reporter though, since I'd never heard of a girl reporter.  At that time, in the 1940's, girls were supposed to become teachers, nurses, or secretaries. In sixth grade I switched again, this time to book editor, which sounded like it might possibly be a career a girl could have. At that time, in the 1940's, girls were supposed to become teachers, nurses, or secretaries. In sixth grade I switched again, this time to book editor, which sounded like it might possibly be a career a girl could have.

Actually, I did become a book editor when I grew up. And some years later, a writer of books. (It wasn't impossible after all, and a girl could do it!) I soon discovered that I liked writing about American history. Not the kind I had to study in school, which seemed to be all about dates and presidents and wars, but about how people lived a long time ago. I'm fascinated by the courage and determination it took for pioneers who settled our country to leave everything they knew behind to start a new life in the wilderness. And I'm intrigued by what it must have been like to live during the American Revolution, with all the upheavals of a new country being born.

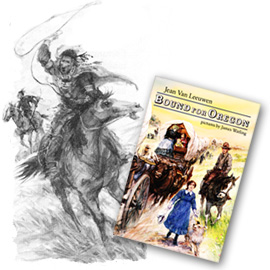

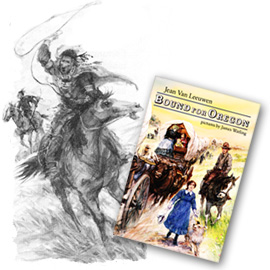

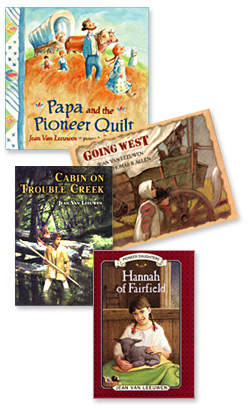

My first book of historical fiction was Going West, a picture book about a family packing up their wagon and moving west to live on the plains. As soon as I began doing research, I got excited. I was finding out so many interesting things—like what a family took with them, how they crossed rivers, built a cabin, planted crops, and dealt with the hardships of their new lives. When I finished that book, I couldn't wait to write another one. There was so much more to find out about those sturdy pioneers! This time, I decided, it would be a longer story about a family moving even farther west, on the Oregon Trail. I called it Bound for Oregon. As soon as I began doing research, I got excited. I was finding out so many interesting things—like what a family took with them, how they crossed rivers, built a cabin, planted crops, and dealt with the hardships of their new lives. When I finished that book, I couldn't wait to write another one. There was so much more to find out about those sturdy pioneers! This time, I decided, it would be a longer story about a family moving even farther west, on the Oregon Trail. I called it Bound for Oregon.

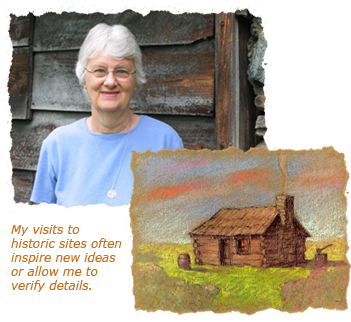

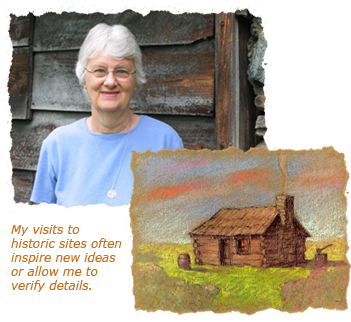

When I begin doing research for a book, it's like going on a great adventure. First, I read everything I can find about the time and place I'll be writing about. The internet is the first place I go, to help me locate materials. Then I take out stacks of books from the library and try to soak in all the information they contain. So I won't forget what I read, I make copies of the parts that seem most important to my story. Pretty soon I have file folders stuffed with facts about clothing and food and furniture and cooking pots and farm chores and wagons and herbal medicine and wool-dyeing and animal-trapping and children's games and 18th-century songs and a zillion other useful (or not so useful) bits of information.

After that, I look in the back of the books I've read. This is where authors of non-fiction tell the sources of their information. Usually credit is given to older books or diaries or letters, written by people who lived in the 1700's or 1800's. That's when I get really excited. My library can often obtain copies of this material for me, sometimes even an actual old book itself. It's a special treat to hold one of these books in my hand—very carefully as the pages can be brittle and the binding coming apart.

But the real thrill is hearing in someone's own words what it was like to travel in a covered wagon on the Oregon Trail or live in a cabin deep in the Ohio woods or witness your town being burned by the British in 1779. You feel as if you were there too. And reading these stories, I've come to realize that being a child in the 1700's, different as it was in so many ways, wasn't different at all in the most important ways. Children then argued with their brothers and sisters, had their feelings hurt, got into mischief and felt sorry, tried to show how brave they were, and were proud when their parents praised them, just like today.

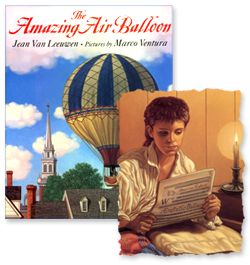

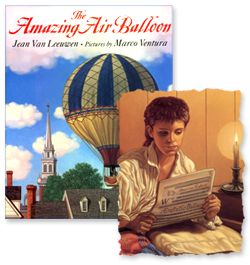

I discover wonderful true stories, which I try to incorporate into my books. Like the one about the spunky young pioneer mother who distracted hostile Indians by feeding them donuts. And the renowned Ohio bear-hunter who lived inside an enormous hollow tree. I've even used true stories I've found during my research as the basis for a book, as I did in The Amazing Air Balloon, the story of a thirteen-year-old boy who was the first person in America to go up in a hot-air balloon.

Sometimes my detective work can lead to a new mystery. While I was working on Bound for Oregon, I learned that children played a game on the trail called "Anti Over the Wagon." That sounded like something fun to include in my story, but how did you play it? What kind of game could be played over a wagon? What were the rules? I looked it up in game books, but couldn't find it. I looked in books about the Oregon Trail, but couldn't find it. I discover wonderful true stories, which I try to incorporate into my books. Like the one about the spunky young pioneer mother who distracted hostile Indians by feeding them donuts. And the renowned Ohio bear-hunter who lived inside an enormous hollow tree. I've even used true stories I've found during my research as the basis for a book, as I did in The Amazing Air Balloon, the story of a thirteen-year-old boy who was the first person in America to go up in a hot-air balloon.

Sometimes my detective work can lead to a new mystery. While I was working on Bound for Oregon, I learned that children played a game on the trail called "Anti Over the Wagon." That sounded like something fun to include in my story, but how did you play it? What kind of game could be played over a wagon? What were the rules? I looked it up in game books, but couldn't find it. I looked in books about the Oregon Trail, but couldn't find it.

When I have a problem like this, I ask questions. I call up experts at historical sites or museums or historical societies and ask them. I spoke to several of these experts, but still couldn't get an answer. I was about to give up when a friend told me about a game her mother remembered from her childhood. It was called "Annie Over" and was played with a ball around a schoolhouse rather than a wagon, but I knew it was the same game.  So I found out the rules and was able to include it in the book. All those hours of research became just one paragraph in my story, but I thought it was worth it. So I found out the rules and was able to include it in the book. All those hours of research became just one paragraph in my story, but I thought it was worth it.

Other times, as hard as I try, I just can't find the answer to one of my questions. All my tracking leads to dead ends. No one knows, not even the experts. Then I have to decide whether I want to spend weeks or months of my life trying to find out something that isn't really necessary to the book, or just leave it out. Often I have to decide, sadly, to leave it out.

Finally—maybe two or three months later—I've gathered all the information I think I need. So I begin writing. Soon I'm caught up in what is happening to my characters. I can see them and their surroundings clearly in my head. I feel like I'm living inside the world of my story. And then a pesky question starts to bother me. "Would she really eat that for breakfast?" Or "Did they wear that kind of hat in the winter back then?" I have to stop writing and find out the answer, hunting through my folders of notes once more or calling an expert on the phone. My research, it seems, is never really finished.

But that is the fun of it. I can see now that when I became a writer of history I actually combined my two early career choices. You need to be something of a detective to track down information about the past. And, after doing all that research, you become a reporter to tell people about it.

I feel so lucky that I enjoy doing both.

|

|

At that time, in the 1940's, girls were supposed to become teachers, nurses, or secretaries. In sixth grade I switched again, this time to book editor, which sounded like it might possibly be a career a girl could have.

At that time, in the 1940's, girls were supposed to become teachers, nurses, or secretaries. In sixth grade I switched again, this time to book editor, which sounded like it might possibly be a career a girl could have. As soon as I began doing research, I got excited. I was finding out so many interesting things—like what a family took with them, how they crossed rivers, built a cabin, planted crops, and dealt with the hardships of their new lives. When I finished that book, I couldn't wait to write another one. There was so much more to find out about those sturdy pioneers! This time, I decided, it would be a longer story about a family moving even farther west, on the Oregon Trail. I called it Bound for Oregon.

As soon as I began doing research, I got excited. I was finding out so many interesting things—like what a family took with them, how they crossed rivers, built a cabin, planted crops, and dealt with the hardships of their new lives. When I finished that book, I couldn't wait to write another one. There was so much more to find out about those sturdy pioneers! This time, I decided, it would be a longer story about a family moving even farther west, on the Oregon Trail. I called it Bound for Oregon.

I discover wonderful true stories, which I try to incorporate into my books. Like the one about the spunky young pioneer mother who distracted hostile Indians by feeding them donuts. And the renowned Ohio bear-hunter who lived inside an enormous hollow tree. I've even used true stories I've found during my research as the basis for a book, as I did in The Amazing Air Balloon, the story of a thirteen-year-old boy who was the first person in America to go up in a hot-air balloon.

Sometimes my detective work can lead to a new mystery. While I was working on Bound for Oregon, I learned that children played a game on the trail called "Anti Over the Wagon." That sounded like something fun to include in my story, but how did you play it? What kind of game could be played over a wagon? What were the rules? I looked it up in game books, but couldn't find it. I looked in books about the Oregon Trail, but couldn't find it.

I discover wonderful true stories, which I try to incorporate into my books. Like the one about the spunky young pioneer mother who distracted hostile Indians by feeding them donuts. And the renowned Ohio bear-hunter who lived inside an enormous hollow tree. I've even used true stories I've found during my research as the basis for a book, as I did in The Amazing Air Balloon, the story of a thirteen-year-old boy who was the first person in America to go up in a hot-air balloon.

Sometimes my detective work can lead to a new mystery. While I was working on Bound for Oregon, I learned that children played a game on the trail called "Anti Over the Wagon." That sounded like something fun to include in my story, but how did you play it? What kind of game could be played over a wagon? What were the rules? I looked it up in game books, but couldn't find it. I looked in books about the Oregon Trail, but couldn't find it. So I found out the rules and was able to include it in the book. All those hours of research became just one paragraph in my story, but I thought it was worth it.

So I found out the rules and was able to include it in the book. All those hours of research became just one paragraph in my story, but I thought it was worth it.